When the Full Moon Rises Over Darjeeling, the Race for the ‘Champagne of Tea’ Begins

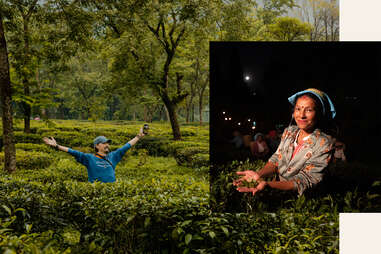

Get up close and personal with India’s ceremoniously harvested Second Flush Tea, one of the region’s most coveted exports.

It’s a balmy night in Darjeeling, India. A Nepalese shaman prepares an altar with a variety of incense, ripe bananas, and floral bouquets amidst a semicircle of chairs. A trio of men start to bang out a beat on percussive instruments. The shaman stills, then erupts into an ecstatic dance.

From there, the transition is lightning fast. There’s a frenetic energy as we pile into a truck. It’s a choppy ride on rugged terrain, and I grasp the dashboard as we skirt the edge of a cliff. The full moon beams overhead, and our driver tells us that if we’re lucky, we might be able to spot some leopards in the near distance. Then we catch sight of our destination: The gentle slope of the tea fields, set ablaze by the Strawberry Full Moon’s golden glow, where a single night’s harvest will soon yield rare and fleeting cups of Darjeeling Second Flush Tea.

Americans have come a long way in understanding and appreciating the origins of the food and drinks we consume. In wine, what was once a choice between white or red has morphed into a qvevri-made orange from Georgia’s Kakheti region, or a pèt-nat from France’s Loire Valley. We went from guzzling $1 cups of bodega coffee, to learning to pronounce “macchiato” at Starbucks, to only settling for micro-roasted beans sourced from a single farm in Colombia. Yet when it comes to tea, many of us Statesiders have barely moved beyond a simple bag of Lipton.

To better understand what goes into a cup of tea—and, ultimately, how tea and tea-drinking culture connects us to the wider world—I was invited to visit Darjeeling, India with Grace Farms, a nonprofit community center based in New Canaan, Connecticut. The foundation transcends easy categorization, its mission to pursue peace through five key pillars: nature, arts, justice, community, and faith. Attached to this pursuit is Grace Farm Foods, a B Corp-certified line of coffees and teas that returns 100% of its profits to Design for Freedom, an initiative committed to ending forced labor worldwide.

Open to the public and housed in a glass property capable of making contemporary architecture nerds swoon, the organization’s Connecticut headquarters is a bit easier to access than Darjeeling. Visitors are welcome to walk in, peruse free exhibits, nature walks, or creative talks, then sit down for a cup of tea. On any given day, resident tea master Frank Kwei might be pouring a cup for a local New Canaanite, an artist, or a representative of the United Nations.

In June, just before the onset of monsoon season, the Grace Farms team and I dove head-first into all things Darjeeling—both the town and its eponymous black tea. Located in the northernmost region of West Bengal, this mountainous Indian municipality (population 162,000) is the stuff of Wes Anderson films, its storied charm inextricably linked to its sheer remoteness. To reach it, we had to fly from New Delhi to Bagdogra—waving hello to Mount Everest from the plane window—then hop in a truck for the three-hour, meandering drive through the emerald, patch-cropped foothills of the Himalayas. And we made that arduous journey in pursuit of one thing: Darjeeling Second Flush Tea.

Known as the “Champagne of teas,” Darjeeling Second Flush Tea is made from the second budding of tea leaves before the monsoon season. Some tea producers believe that, as a result of biodynamic farming practices, the full moon’s gravitational pull heightens the plant’s muscatel, a honey-like flavor that’s difficult to measure or describe. Gathering the leaves under these cosmic circumstances is more of a spiritual ritual than a regular agricultural shift, and is reserved for only the best pickers. Each year, Grace Farms sends its staff to Darjeeling to participate in the event. Afterwards, they’re tasked with bringing the tea back to the US where they’ll package and sell it as a limited-release product.

“We’re traveling halfway around the world to experience this one particular evening,” Kwei explained as we weaved through the mist. “All the conditions need to be ideal—cloud cover, rainfall, so on, and so forth. Everything is up to the gods, if you will.”

As we ascended the hillside, passing cars beeping in a quotidian fight for space, I caught sight of a line of women returning home from working in the fields. They moved as an assembly of color, sporting pretty, patterned head wraps while balancing elegant parasols and massive woven baskets teeming with piles of green leaves. A few looked up at us to say hello, their faces revealing strikingly bright orange-red lipstick.

Earlier that day, Jeewan Prakash Gurung, fondly known in the Darjeeling tea community as JP, had gone out of his way to pick us up from the Bagdogra airport. “There is something special about this place,” Gurung said, during a much-needed pit-stop to load up on roadside momos. “It could be the terrain, it could be the people, it could be the cool Himalayan breeze. But go to anybody's house in Darjeeling, and the first thing they'll offer you is a cup of tea. Whether they know you or not? Immaterial.”

Born into a family of tea farmers, Gurung followed in his father’s footsteps working for various tea estates in Darjeeling throughout the ‘70s. Today, he serves as an advisor and consultant for an industry advocacy group called Tea Promoters India, or TPI. Throughout his long career—as documented in his books All In a Cup of Tea and Muscatel Memories—Gurung has seen firsthand how India’s tea landscape has evolved and transformed. His presence is strong, solid—The temperature changes when Gurung, who’s never without a handsome hat, enters the room. When he speaks, people listen, yet any hint of intimidation is wiped away as soon as he flashes his cheeky grin.

A true teller of tales, industry vet Gurung is delighted to answer all our tea-related questions. The next morning, we gathered around the front porch of Selimbong Tea Garden, a colonial-era bungalow perched on a bluff overlooking the expanse of neighboring farms. As Gurung launched into a lesson in local history, I could hear Kwei dramatically slurping his tea, adopting the same retronasal olfactory technique employed by wine connoisseurs.

According to Gurung, it all started in the mid-1800s, when the British-controlled East India Company, seeking a source of tea outside of China, found that the plant thrived in Darjeeling’s subtropical, highland climate. When India gained independence in 1947, the estates were sold to Indian businesses, and, almost a hundred years after the industry’s inception, trade unionism was introduced. Today, however, there are still echoes of British rule, as many tea pickers continue to face harsh working conditions.

Tea gardens in India are now owned by the state, and the land is leased to local management companies who are responsible for the care of their employees. Grace Farms chooses to partner with TPI because of its outspoken commitment to organic and Fairtrade farming practices. And this trip was an opportunity for Adam Thatcher, CEO of Grace Farms Foods, to see for himself how those ethical standards were being implemented, from expanded sanitation services to women empowerment workshops. (As Gurung proudly noted, TPI is the only company in the district of Darjeeling with a woman garden manager on staff.)

Later, Kwei, who once owned his own premium tea company, led me on a stroll through the verdant gardens, going over the basics as we brushed our hands over waist-high bushes. The word “tea” is often used as a catch-all for anything steeped in boiling water, but only white, green, black, and oolong tea can be classified as such, because they come from the camellia sinensis plant. The shrub produces naturally caffeinated leaves, and depending on the way the leaves are oxidized and processed, it can produce a variety of teas.

Black and green tea, for instance, are born from the same leaf, the difference being that the former is oxidized while the latter isn’t. You can make a tea-like tincture out of things that don’t come from camellia sinensis—flowers, leaves, roots, bark, and seeds—but in this case, they’re considered herbal teas.

In the same way that French wines are named after their regions of origin, Darjeeling tea is a black tea grown in Darjeeling. It also offers a wine-like complexity—musky, filled with tannins, and verging on fruity. In 2004, Darjeeling tea became the first Indian product to be protected under geographical indication (GI) status—only 87 gardens under the District of Darjeeling are entitled to use the term.

With other types of farming, the harvest process is simple: When the crop is ready, you pick it. But with tea leaves, the flavor profile changes by the day, and each day makes for a different kind of tea. The Second Flush, for instance, is famous for its “tippy” teas, or a cluster of newly budding leaves marked by silver tips. These teas tend to have a more delicate flavor and aroma—a far cry from your average Earl Grey or English Breakfast.

“Lipton is a success story, but it comes from a very different angle: consistency. Every single bag needs to taste exactly the same—they have proprietary blends and a flavor profile that their tea suppliers need to match, year in and year out,” Kwei said. In Darjeeling, he explained, assessing tea is broken down into year, region, garden, day, and lot. “A ‘lot’ is a batch of tea picked on a specific day, in a particular garden, with a particular group of plants. There are hundreds and thousands of lots of the same tea, and JP's job is to literally taste thousands of these teas to figure out the flaws, nuances, and characteristics.”

"Go to anybody's house in Darjeeling, and the first thing they'll offer you is a cup of tea. Whether they know you or not? Immaterial."

Tea pickers, the majority of whom are women because their fingers are considered more nimble, must pick about 10,000 shoots to produce one kilogram of green leaf. Once the moisture is removed and the leaves are fermented, the result shrinks down to about 250 grams. Then it’s sieved, and you’re left with 125 grams of drinkable tea. That means it takes bushels upon bushels of shoots to make just half a cup of tea.

With those kinds of margins, it’s clear that money isn’t the central motivating factor for tea farmers like Gurung. Rather, they’re drawn by a reverence to a tradition that’s been around for over a century, and sadly, one that’s institutional knowledge is increasingly at stake. As seasoned tea producers pass away, the few younger individuals brave enough to enter the business face an onslaught of unforeseen problems: aging bushes, declining yields due to climate change, the economic downturn brought about by COVID-19, uneducated consumers, and fierce competition within the global market, to name a few.

For Gurung, it’s not just about marketing. Tea is fundamental to understanding Darjeeling and its people. “We are not dealing with a commodity,” he said. “We are dealing with something that has been specially crafted, that has exploited the virtues of nature to the hilt, and we are bringing that to you, not as a cup of tea, but as an experience.”

In 1924, an Austrian man named Rudolf Steiner proposed a closed-loop system of fertility, in which the physical and spiritual world would align. Today, Steiner’s biodynamic farming is practiced worldwide by operations both big and small. The style bans the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, and might involve unconventional measures like treating compost with medicinal preparations to encourage microbial life, or packing manure into cow horns and burying them into the earth. Tonight in Darjeeling, it’s about paying particular attention to planetary positioning, namely the appearance of the Strawberry Full Moon.

“Will tonight's tea be the best tea in the world? I don't know. It may not be, but that’s not the point,” Kwei says, as the truck slows to a stop and we tumble out, gazes fixed on the tea fields in front of us. That morning, however, we woke to a good omen: The sight of wild pink lilies sprouted among the tea plants, a phenomenon the garden manager says happens only in anticipation of the celestial event. “The thing is, once you trust the experience—the effort that you put into honoring this day, honoring the culture—there’s not a doubt in my mind that the tea made from the leaves picked tonight will be exceptional.”

Backlit by the looming moon, a group of women armed with torches begin to descend the hill of the tea garden. They’re suddenly rushing past us to pick the leaves that will be processed that same night. We’re all caught up in the throng, eyes fixed on the way the master pickers twirl the leaves in their fingers with swift finesse.

It’s all over in less than an hour. The pickers take turns dumping their piles onto a large scale outside the factory as a team of men crouch around, recording the night’s numbers in a notebook. Tomorrow morning, we’ll get to taste the tea. But for now, we return back to the house, where we gather around a bonfire and listen to Gurung share some stories.

After some gin-induced reflection, I ask Gurung what his hopes are for the future of Darjeeling. “I would like to actually request that Grace Farms, in due course of time, conduct tea tours for American tea lovers,” Gurung says. “The sharing of an experience is always better than sharing through words.”

It’s an ironic thing to say for a man with two books and endless stories under his belt, but he has a point. All the effort it took to get here—a 17-hour flight, off-roading through leopard-laden hills, the trust we placed in the moon’s cosmic influence—made that first sip of Second Flush all the more worth it… regardless of whether or not my unrefined, American palate could really taste the difference.